The history of the competition among major types of US piston propliners is an interesting story of ever increasing speed and range. It was widely held that if a 20 minute difference existed on a given route, passengers would invariably book flights on the faster plane. Thus speed was the number one issue, followed by range - since non stop flights often got there faster than flights that had to stop. However, before the mid 1950's it was widely assumed that people wanted to get out and stretch their legs every few hours, so this was not such a selling point on domestic routes.

The Boeing 247: The modern era of the airline industry is generally

thought to have begun with the introduction of the Boeing 247 in 1933, the first

all-metal cantilever twin engine airliner that was commercially successful.

It held 10 passengers, cruising at a speed of 160 mph. The big problem with

the plane was not the plane itself, but the fact that airlines other than United

couldn't buy any. Boeing Aircraft was owned by the same company that owned United

Air Lines, and had committed the first 60 aircraft to them. Thus, other airlines

like TWA were unable to purchase the plane.

The Boeing 247: The modern era of the airline industry is generally

thought to have begun with the introduction of the Boeing 247 in 1933, the first

all-metal cantilever twin engine airliner that was commercially successful.

It held 10 passengers, cruising at a speed of 160 mph. The big problem with

the plane was not the plane itself, but the fact that airlines other than United

couldn't buy any. Boeing Aircraft was owned by the same company that owned United

Air Lines, and had committed the first 60 aircraft to them. Thus, other airlines

like TWA were unable to purchase the plane.

The Douglas

DC-3: Since TWA couldn't purchase the 247, they sent out proposals

to other aircraft manufacturers for a similar plane (although they originally

specified a trimotor). Douglas and General Aircraft were the only respondents

and while General's proposal was for a traditional trimotor, Douglas wanted

to build a modern twin engine aircraft much like the 247, but bigger and faster.

TWA ordered one of each. When TWA tested the new DC-1 the General trimotor was

quickly cancelled, and TWA ordered the slightly stretched DC-2 into production.

However, the series really came of age when American Airlines wanted a wider

fuselage to hold their berths, used on their longer route's overnight flights.

Douglas responded in 1935 with the DC-3 with 900 hp engines, which held 21 seats

in the day version and flew at 170 mph. Thus, while not much faster than the

247, the plane held twice as many passengers. This was the first plane that

could make money for the airlines on passengers alone, although mail continued

to be a very important money maker. Even United had to give in and buy DC-3's

to stay competitive. Through WWII the DC-3 flew over 50% of the world's passengers,

and in the USA it was closer to 90%. During WWII, the DC-3 (the Dakota) was

produced in huge numbers (over 10,000) for use as troop transports.

The Douglas

DC-3: Since TWA couldn't purchase the 247, they sent out proposals

to other aircraft manufacturers for a similar plane (although they originally

specified a trimotor). Douglas and General Aircraft were the only respondents

and while General's proposal was for a traditional trimotor, Douglas wanted

to build a modern twin engine aircraft much like the 247, but bigger and faster.

TWA ordered one of each. When TWA tested the new DC-1 the General trimotor was

quickly cancelled, and TWA ordered the slightly stretched DC-2 into production.

However, the series really came of age when American Airlines wanted a wider

fuselage to hold their berths, used on their longer route's overnight flights.

Douglas responded in 1935 with the DC-3 with 900 hp engines, which held 21 seats

in the day version and flew at 170 mph. Thus, while not much faster than the

247, the plane held twice as many passengers. This was the first plane that

could make money for the airlines on passengers alone, although mail continued

to be a very important money maker. Even United had to give in and buy DC-3's

to stay competitive. Through WWII the DC-3 flew over 50% of the world's passengers,

and in the USA it was closer to 90%. During WWII, the DC-3 (the Dakota) was

produced in huge numbers (over 10,000) for use as troop transports.

. The Douglas

DC-4 Skymaster: While the DC-3 was a very competent airliner, it didn't

have the range required for flying across oceans, or even continents. To fly

across the USA required 3 stops, and a gruelling 17 hours. Thus, the US airlines

got together and funded a Douglas study for a larger, 4 engine airliner. After

first coming up with a plane that was too large, too slow, and too complicated

(the original DC-4, later the DC-4E), Douglas scaled down the plane and came

up with the much simpler DC-4, equipped with 1450 hp R-2000 engines. Ordered

into production for 1942, the DC-4 looked like a winner, flying 44 passengers

at 225 mph. However, WWII intervened, and all DC-4's of the time were taken

by the military as C-54's and used to fly supplies over the Atlantic and other

oceans to the war. The military wanted as many as Douglas could produce (at

the main Douglas plant in Santa Monica, CA, and a new plant in Chicago by Orchard

Field, which later became O'Hare - that's why its letters are ORD - Orchard/Douglas

airport) and over a thousand DC-4's were delivered. After the war, 79 DC-4's

were produced for civil customers, but hundreds of surplus military C-54's were

converted to airline use and used all over the world. Passengers marvelled at

flying across the USA with one stop in only 14 hours!

. The Douglas

DC-4 Skymaster: While the DC-3 was a very competent airliner, it didn't

have the range required for flying across oceans, or even continents. To fly

across the USA required 3 stops, and a gruelling 17 hours. Thus, the US airlines

got together and funded a Douglas study for a larger, 4 engine airliner. After

first coming up with a plane that was too large, too slow, and too complicated

(the original DC-4, later the DC-4E), Douglas scaled down the plane and came

up with the much simpler DC-4, equipped with 1450 hp R-2000 engines. Ordered

into production for 1942, the DC-4 looked like a winner, flying 44 passengers

at 225 mph. However, WWII intervened, and all DC-4's of the time were taken

by the military as C-54's and used to fly supplies over the Atlantic and other

oceans to the war. The military wanted as many as Douglas could produce (at

the main Douglas plant in Santa Monica, CA, and a new plant in Chicago by Orchard

Field, which later became O'Hare - that's why its letters are ORD - Orchard/Douglas

airport) and over a thousand DC-4's were delivered. After the war, 79 DC-4's

were produced for civil customers, but hundreds of surplus military C-54's were

converted to airline use and used all over the world. Passengers marvelled at

flying across the USA with one stop in only 14 hours!

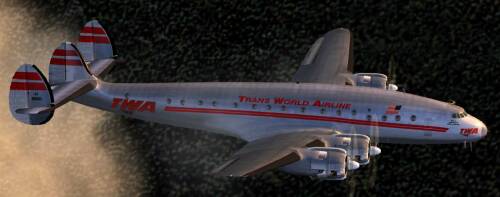

The Lockheed

L-049 Constellation: The reason that Douglas didn't sell many DC-4's

after the war came from the competition of this plane, the famous Connie. A

brainchild of Howard Hughes and TWA, it was designed as the first pressurized

airliner that could fly above the weather, based on the pioneering efforts of

Tommy Tomlinson at that airline. The daring choice to use engines not even off

the drawing board at that point gave the plane great speed, and could transport

50 passengers at 313 mph. Lockheed and TWA gambled that the engines (2200 hp

R-3350's) would be ready, based on the fact that they were planned to be installed

in the B-29, a very important plane to the US military and thus assured of high

priority in testing and development. While the plane was developed starting

in 1941, the military-designated C-69 was given low priority during WWII, and

wasn't really ready until 1945. When the war ended, the military cancelled almost

all of their orders and thus Lockheed was ready to provide an aircraft clearly

superior to the DC-4 in late 1945. Hughes had extracted a promise from Lockheed

not to sell any to airlines competing with TWA, but the war and other factors

diluted this restriction. TWA was still the first to put the Connie into service,

and although just a converted C-69, the L-049 was still far better than what

United and American were flying, the DC-4. Compared to the DC-4's 14 hours across

the US, the Connie could do it in 11. Remember the 20 minute rule - this was

a 3 hour difference! And even more important, while the DC-4 was slogging through

storms at 10,000 ft, the pressurized L-049 could be flying above the weather

at 20,000 ft. Many other airlines around the world initiated their first postwar

international services with the L-049, or quickly switched from the DC-4 to

the new Connie.

The Lockheed

L-049 Constellation: The reason that Douglas didn't sell many DC-4's

after the war came from the competition of this plane, the famous Connie. A

brainchild of Howard Hughes and TWA, it was designed as the first pressurized

airliner that could fly above the weather, based on the pioneering efforts of

Tommy Tomlinson at that airline. The daring choice to use engines not even off

the drawing board at that point gave the plane great speed, and could transport

50 passengers at 313 mph. Lockheed and TWA gambled that the engines (2200 hp

R-3350's) would be ready, based on the fact that they were planned to be installed

in the B-29, a very important plane to the US military and thus assured of high

priority in testing and development. While the plane was developed starting

in 1941, the military-designated C-69 was given low priority during WWII, and

wasn't really ready until 1945. When the war ended, the military cancelled almost

all of their orders and thus Lockheed was ready to provide an aircraft clearly

superior to the DC-4 in late 1945. Hughes had extracted a promise from Lockheed

not to sell any to airlines competing with TWA, but the war and other factors

diluted this restriction. TWA was still the first to put the Connie into service,

and although just a converted C-69, the L-049 was still far better than what

United and American were flying, the DC-4. Compared to the DC-4's 14 hours across

the US, the Connie could do it in 11. Remember the 20 minute rule - this was

a 3 hour difference! And even more important, while the DC-4 was slogging through

storms at 10,000 ft, the pressurized L-049 could be flying above the weather

at 20,000 ft. Many other airlines around the world initiated their first postwar

international services with the L-049, or quickly switched from the DC-4 to

the new Connie.

The Douglas

DC-6 Cloudmaster: As soon as the airlines competing with TWA (or competing

with the other airlines that had ordered the new Connie) realized that their

DC-4's would be hopelessly outclassed by the L-049, they began searching for

a plane that could match or exceed the Connie. Many tried to order the Connie

itself, only to be told that they would have to get in line behind the early

converts. Thus, they turned to other manufacturers. Douglas was a logical choice,

and they had a plane in mind. During WWII, they offered the military the option

of a much improved DC-4, with greater speed and range, and pressurized to boot,

equipped with reliable 2100 hp R-2800 engines. While the AAF wasn't too interested,

they did let Douglas prepare a prototype of the plane, the XC-112. However,

given low priority, it didn't go beyond this point. What Douglas realized was

that this could be the starting point for the next DC airliner (after the aborted

short range DC-5, cancelled just before the war due to military commitments

at the El Segundo, CA plant where it was to be produced). This then resulted

in the DC-6, which was quickly ordered by the airlines that hadn't ordered the

Connie and became available about a year after the L-049. It was a little faster

than the Connie, but also had a much better interior and air conditioning system.

It could do the US transcon route (still with 1 stop) in about 10 hours, about

an hour faster than the Connie, and also flew above the weather.

The Douglas

DC-6 Cloudmaster: As soon as the airlines competing with TWA (or competing

with the other airlines that had ordered the new Connie) realized that their

DC-4's would be hopelessly outclassed by the L-049, they began searching for

a plane that could match or exceed the Connie. Many tried to order the Connie

itself, only to be told that they would have to get in line behind the early

converts. Thus, they turned to other manufacturers. Douglas was a logical choice,

and they had a plane in mind. During WWII, they offered the military the option

of a much improved DC-4, with greater speed and range, and pressurized to boot,

equipped with reliable 2100 hp R-2800 engines. While the AAF wasn't too interested,

they did let Douglas prepare a prototype of the plane, the XC-112. However,

given low priority, it didn't go beyond this point. What Douglas realized was

that this could be the starting point for the next DC airliner (after the aborted

short range DC-5, cancelled just before the war due to military commitments

at the El Segundo, CA plant where it was to be produced). This then resulted

in the DC-6, which was quickly ordered by the airlines that hadn't ordered the

Connie and became available about a year after the L-049. It was a little faster

than the Connie, but also had a much better interior and air conditioning system.

It could do the US transcon route (still with 1 stop) in about 10 hours, about

an hour faster than the Connie, and also flew above the weather.

The Lockheed

L-749 Constellation: Once Lockheed realized that Douglas had matched

and even slightly exceeded its original offering, they quickly decided to upgrade

the interior and air conditioning systems, along with several other improvements,

such as more powerful engines for greater speed and more fuel for greater range.

This then resulted in the L-649 in 1947, quickly followed by the L-749 and L-749A

(most earlier versions were converted to the L-749A standard within a few years).

The "Gold Plate" Connie could match the DC-6 in almost every respect,

and had significantly greater range. Many consider the L-749A as the finest

Connie ever built - reasonably reliable, and the passengers loved it. Most airlines

with international routes chose the new Connie over the DC-6 if they needed

the extra range, although for most domestic airlines the choice tended to be

the DC-6, with slightly better economics and simplicity. For example, the Connie's

control system (hydraulic boost) was much more complicated than the Doug's aerodynamic

tabs.

The Lockheed

L-749 Constellation: Once Lockheed realized that Douglas had matched

and even slightly exceeded its original offering, they quickly decided to upgrade

the interior and air conditioning systems, along with several other improvements,

such as more powerful engines for greater speed and more fuel for greater range.

This then resulted in the L-649 in 1947, quickly followed by the L-749 and L-749A

(most earlier versions were converted to the L-749A standard within a few years).

The "Gold Plate" Connie could match the DC-6 in almost every respect,

and had significantly greater range. Many consider the L-749A as the finest

Connie ever built - reasonably reliable, and the passengers loved it. Most airlines

with international routes chose the new Connie over the DC-6 if they needed

the extra range, although for most domestic airlines the choice tended to be

the DC-6, with slightly better economics and simplicity. For example, the Connie's

control system (hydraulic boost) was much more complicated than the Doug's aerodynamic

tabs.

The Boeing

377 Stratocruiser: While Lockheed and Douglas were battling over who

could produce the airliner with the best economics, Pan American and Boeing

went a different way - they set out to produce the most luxurious long range

airliner possible, and still make money. The result in 1949 was the ponderous

looking but yet elegant Stratocruiser, a plane that was in a class of its own.

Based on many components from the B-29, it could whisk 60 passengers up to 3000

miles in great comfort at over 300 mph, due to its huge 3500 hp R-4360 Wasp

Major engines. It's best known for the spiral staircase leading to a lower level

lounge, which provided a nice break from the tedium of the trip. Berths were

typically provided for overnight trips, which the commodious fuselage easily

accommodated. So the big question is: why weren't more than 55 produced? The

answer could be described in one word - money. Not only were they expensive

to buy, they were very expensive to run. Even with all first class seats and

berths, they usually still did not make their owners much profit. However, they

were dearly loved by passengers, and once an airline flying the Atlantic or

the Pacific owned them they could not give them up for fear that their competition

(who often were flying Stratocruisers of their own) would take most of their

passengers away. Not until the DC-7C provided much faster flight times on long

routes did the Strat's replacement begin. Such luxury, begun on the great Pan

American flying boats, was never seen again.

The Boeing

377 Stratocruiser: While Lockheed and Douglas were battling over who

could produce the airliner with the best economics, Pan American and Boeing

went a different way - they set out to produce the most luxurious long range

airliner possible, and still make money. The result in 1949 was the ponderous

looking but yet elegant Stratocruiser, a plane that was in a class of its own.

Based on many components from the B-29, it could whisk 60 passengers up to 3000

miles in great comfort at over 300 mph, due to its huge 3500 hp R-4360 Wasp

Major engines. It's best known for the spiral staircase leading to a lower level

lounge, which provided a nice break from the tedium of the trip. Berths were

typically provided for overnight trips, which the commodious fuselage easily

accommodated. So the big question is: why weren't more than 55 produced? The

answer could be described in one word - money. Not only were they expensive

to buy, they were very expensive to run. Even with all first class seats and

berths, they usually still did not make their owners much profit. However, they

were dearly loved by passengers, and once an airline flying the Atlantic or

the Pacific owned them they could not give them up for fear that their competition

(who often were flying Stratocruisers of their own) would take most of their

passengers away. Not until the DC-7C provided much faster flight times on long

routes did the Strat's replacement begin. Such luxury, begun on the great Pan

American flying boats, was never seen again.

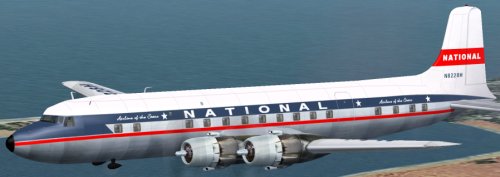

The Douglas

DC-6B Super Cloudmaster: After Lockheed came out with the L-749A, Douglas

decided (after Pratt & Whitney announced that more powerful 2400 hp R-2800

engines would soon be available) to produce a more economical airliner by stretching

the DC-6 to add more passenger seats. This resulted in the DC-6B of 1951 which,

while flying no faster or farther than the DC-6, allowed the airline owner to

lower the cost per seat for a given trip. This led to the DC-6B often being

used in "Tourist" class service, resulting in airlines increasing

their passenger count by catering to travelers that couldn't fly before due

to the high cost. It is generally thought that the DC-6B was the most economical

long range piston airliner ever built. For those that used it in first class

service, it was instead gratifyingly profitable. :) Either way, Douglas had

a winner, and customers flocked to buy it - almost every major US airline except

Delta (committed to the DC-7), Eastern and TWA (both committed to the Connie)

purchased the DC-6B as well as many airlines around the world. Its wonderful

thriftiness kept it in service until very recently.

The Douglas

DC-6B Super Cloudmaster: After Lockheed came out with the L-749A, Douglas

decided (after Pratt & Whitney announced that more powerful 2400 hp R-2800

engines would soon be available) to produce a more economical airliner by stretching

the DC-6 to add more passenger seats. This resulted in the DC-6B of 1951 which,

while flying no faster or farther than the DC-6, allowed the airline owner to

lower the cost per seat for a given trip. This led to the DC-6B often being

used in "Tourist" class service, resulting in airlines increasing

their passenger count by catering to travelers that couldn't fly before due

to the high cost. It is generally thought that the DC-6B was the most economical

long range piston airliner ever built. For those that used it in first class

service, it was instead gratifyingly profitable. :) Either way, Douglas had

a winner, and customers flocked to buy it - almost every major US airline except

Delta (committed to the DC-7), Eastern and TWA (both committed to the Connie)

purchased the DC-6B as well as many airlines around the world. Its wonderful

thriftiness kept it in service until very recently.

The Lockheed

L-1049 Super Constellation: Lockheed was not about to be outclassed

by Douglas' DC-6B, and immediately started to perform a similar stretch to the

Connie to create the new Super Connie, available soon after the DC-6B in 1951.

While it was hoped that the plane could be as fast as the upcoming competition,

this early version was still powered by standard R-3350 engines and thus it

was a little slower than the upcoming DC-7. Once American announced that it

would be starting nonstop transcon flights across the USA with the DC-7, so

TWA decided to try it first with their new L-1049's. Why no nonstops before

this? The DC-6's and L-749's had always had enough range for the nonstop trip

(they flew to Hawaii, after all), so what was the problem? The problem was that

they took longer than 8 hours and the pilot's union rules stated that 8 hour

flights were the maximum without a relief crew - and two crews onboard would

be uneconomical. However, once American had announced their nonstop flights

across the country with their upcoming DC-7, TWA convinced the pilots (with

incentives) to try it with their new L-1049 Super Connies, and it was a great

success. Nonstop across the US in only 9 hours, TWA's Ambassador service brought

passengers from the competition in droves. (Yes I know QANTAS didn't have any

of these).

The Lockheed

L-1049 Super Constellation: Lockheed was not about to be outclassed

by Douglas' DC-6B, and immediately started to perform a similar stretch to the

Connie to create the new Super Connie, available soon after the DC-6B in 1951.

While it was hoped that the plane could be as fast as the upcoming competition,

this early version was still powered by standard R-3350 engines and thus it

was a little slower than the upcoming DC-7. Once American announced that it

would be starting nonstop transcon flights across the USA with the DC-7, so

TWA decided to try it first with their new L-1049's. Why no nonstops before

this? The DC-6's and L-749's had always had enough range for the nonstop trip

(they flew to Hawaii, after all), so what was the problem? The problem was that

they took longer than 8 hours and the pilot's union rules stated that 8 hour

flights were the maximum without a relief crew - and two crews onboard would

be uneconomical. However, once American had announced their nonstop flights

across the country with their upcoming DC-7, TWA convinced the pilots (with

incentives) to try it with their new L-1049 Super Connies, and it was a great

success. Nonstop across the US in only 9 hours, TWA's Ambassador service brought

passengers from the competition in droves. (Yes I know QANTAS didn't have any

of these).

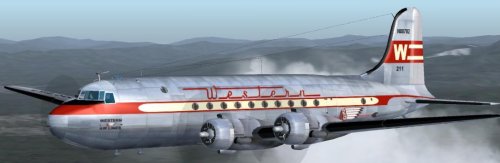

The Douglas

DC-7: After TWA ordered the L-1049 Super Connie, American's CR Smith

was apparently very apprehensive that TWA would start nonstop service and take

most of American's passengers away from their DC-6B's, which still required

a stop. He convinced a skeptical Douglas that hanging the upcoming 3250 hp Turbo-Compound

R-3350 engines onto a slightly stretched DC-6B and increasing the fuel load

would result in a plane that could do the job, and ordered 25 examples to seal

the deal. The DC-7 could take 65 passengers across the country at more than

350 mph, resulting in a flight time of around 8 hours - long a goal of the airlines

to meet the pilot's union rules. When delivered in 1953, it quickly brought

the passengers that had switched to TWA's Ambassador service right back to American's

Mercury service. United was not as certain that nonstop service was worth the

cost of a plane with considerably poorer economics than its beloved DC-6B, but

soon realized that flying DC-7's was still more profitable than flying empty

DC-6B's.

The Douglas

DC-7: After TWA ordered the L-1049 Super Connie, American's CR Smith

was apparently very apprehensive that TWA would start nonstop service and take

most of American's passengers away from their DC-6B's, which still required

a stop. He convinced a skeptical Douglas that hanging the upcoming 3250 hp Turbo-Compound

R-3350 engines onto a slightly stretched DC-6B and increasing the fuel load

would result in a plane that could do the job, and ordered 25 examples to seal

the deal. The DC-7 could take 65 passengers across the country at more than

350 mph, resulting in a flight time of around 8 hours - long a goal of the airlines

to meet the pilot's union rules. When delivered in 1953, it quickly brought

the passengers that had switched to TWA's Ambassador service right back to American's

Mercury service. United was not as certain that nonstop service was worth the

cost of a plane with considerably poorer economics than its beloved DC-6B, but

soon realized that flying DC-7's was still more profitable than flying empty

DC-6B's.

The Lockheed

L-1049G Super Constellation: TWA and other Connie users were of course

none too happy about the DC-7's extra speed, and convinced Lockheed that they

needed something better. Lockheed responded with the L-1049C and L-1049E, both

powered by the new Turbo-Compound R-3350's. This narrowed the gap (and TWA ordered

L-1049E's), but TWA was also looking for something more - greater range. This

resulted in the L-1049G, the "Super G", delivered in 1955. The best

of the Super Connies, it was able to fly nonstop across the country westbound

even against the most severe headwinds, which occasionally required the DC-7's

to make a technical stop for fuel. However, disappointingly it was still a little

slower than the DC-7 but this could be minimized by sacrificing fuel consumption

and flying at higher power levels. It did usher in a new era in transatlantic

flight, often allowing nonstop service on many of the shorter routes, as long

as there were no significant headwinds. Very popular with passengers due to

its luxurious interiors (often including berths), it served the airlines well.

The Lockheed

L-1049G Super Constellation: TWA and other Connie users were of course

none too happy about the DC-7's extra speed, and convinced Lockheed that they

needed something better. Lockheed responded with the L-1049C and L-1049E, both

powered by the new Turbo-Compound R-3350's. This narrowed the gap (and TWA ordered

L-1049E's), but TWA was also looking for something more - greater range. This

resulted in the L-1049G, the "Super G", delivered in 1955. The best

of the Super Connies, it was able to fly nonstop across the country westbound

even against the most severe headwinds, which occasionally required the DC-7's

to make a technical stop for fuel. However, disappointingly it was still a little

slower than the DC-7 but this could be minimized by sacrificing fuel consumption

and flying at higher power levels. It did usher in a new era in transatlantic

flight, often allowing nonstop service on many of the shorter routes, as long

as there were no significant headwinds. Very popular with passengers due to

its luxurious interiors (often including berths), it served the airlines well.

The Douglas

DC-7B: While negotiating for the L-1049E (later to be converted to

Super G's), Douglas offered TWA an improved DC-7 with more range, allowed by

the incorporation of nacelle "saddle tanks" for more fuel. While TWA

eventually selected the Super G, Douglas offered the new DC-7B to other airlines

and Pan American and South African signed up. Airlines other than PAA and SAA

didn't need the extra range and they bought their DC-7B's for the other improvements

but without the saddle tanks. The DC-7B was considered the fastest of the Douglas

propliners, and could cruise at over 360 mph when delivered in 1955. However,

its range did not quite match the L-1049G, and it was insufficient for many

ocean crossings to be made nonstop.

The Douglas

DC-7B: While negotiating for the L-1049E (later to be converted to

Super G's), Douglas offered TWA an improved DC-7 with more range, allowed by

the incorporation of nacelle "saddle tanks" for more fuel. While TWA

eventually selected the Super G, Douglas offered the new DC-7B to other airlines

and Pan American and South African signed up. Airlines other than PAA and SAA

didn't need the extra range and they bought their DC-7B's for the other improvements

but without the saddle tanks. The DC-7B was considered the fastest of the Douglas

propliners, and could cruise at over 360 mph when delivered in 1955. However,

its range did not quite match the L-1049G, and it was insufficient for many

ocean crossings to be made nonstop.

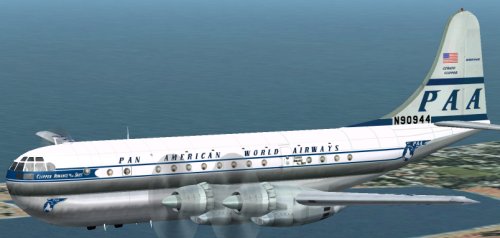

The Douglas

DC-7C Seven Seas: Douglas was not able to match the Super G with the

DC-7B, and Pan American was still not able to fly across the Atlantic nonstop

all of the time. PAA President Juan Trippe let Douglas know that they wouldn't

settle for less, if Douglas wanted its business. Wright's announcement of more

powerful 3400 hp R-3350 engines allowed Douglas to increase the weight (and

thus fuel load) of the DC-7B. To house this extra fuel, Douglas extended the

wing roots by 5 feet each, also putting the rather noisy Wright engines further

out on the wing. They also stretched the front fuselage to accommodate an extra

seat row, improving the economics of the plane. This resulted in the DC-7C Seven

Seas, delivered in 1956, which for the first time allowed nonstop trips across

the Atlantic in either direction in any weather. It also allowed nonstop trips

to be made to places further away, like New York to Rome, as well as opening

up polar routes like Copenhagen-Tokyo and Los Angeles-London.

The Douglas

DC-7C Seven Seas: Douglas was not able to match the Super G with the

DC-7B, and Pan American was still not able to fly across the Atlantic nonstop

all of the time. PAA President Juan Trippe let Douglas know that they wouldn't

settle for less, if Douglas wanted its business. Wright's announcement of more

powerful 3400 hp R-3350 engines allowed Douglas to increase the weight (and

thus fuel load) of the DC-7B. To house this extra fuel, Douglas extended the

wing roots by 5 feet each, also putting the rather noisy Wright engines further

out on the wing. They also stretched the front fuselage to accommodate an extra

seat row, improving the economics of the plane. This resulted in the DC-7C Seven

Seas, delivered in 1956, which for the first time allowed nonstop trips across

the Atlantic in either direction in any weather. It also allowed nonstop trips

to be made to places further away, like New York to Rome, as well as opening

up polar routes like Copenhagen-Tokyo and Los Angeles-London.

The Lockheed

L-1649A Starliner: The DC-7C quickly garnered orders from the majority

of the world's major international airlines, including a few that had previously

ordered Connies for transatlantic service. While Lockheed wasn't interested

in producing another piston airliner, they did feel that a turboprop would be

able to leap ahead of the competing DC-7C. Thus they created a new high performance

wing, and planned for yet untested P&W turboprop engines to hang on them.

This was the L-1449, which would have been an impressive plane. TWA ordered

25 of them, and looked forward to beating the Seven Seas by late 1956. However,

it turned out that the engines were not working out well in testing, alternative

Allison 501's (the L-1549) would have even worse economics, and thus had to

be replaced with the same R-3350's used on the DC-7C. This, along with Lockheed's

unwillingness to stretch the fuselage to hold more passengers, led to alarming

economic forecasts for the plane, now designated the L-1649A Starliner. However,

Howard Hughes had already committed the funds to allow a big tax break for the

year, and would not allow Lockheed or TWA to cancel the order. Lockheed could

find only two more buyers, and it turned out to be a big money loser. On top

of that, the engine change had caused it to be delayed - not being delivered

until 1957, less than a year away from the first US jets. The final blow was

that it turned out to be slower than the DC-7C, but luckily not by much. However,

the Starliner had one redeeming quality - its unmatched range. This allowed

TWA to provide nonstop service to all European cities from half of the USA,

and its polar service was impressive. Its high allowed loads on these long flights

improved the economics somewhat, but it still turned out to be inferior to those

of the Seven Seas. It was very popular with passengers, though, and was known

as the "Queen of the Skies".

The Lockheed

L-1649A Starliner: The DC-7C quickly garnered orders from the majority

of the world's major international airlines, including a few that had previously

ordered Connies for transatlantic service. While Lockheed wasn't interested

in producing another piston airliner, they did feel that a turboprop would be

able to leap ahead of the competing DC-7C. Thus they created a new high performance

wing, and planned for yet untested P&W turboprop engines to hang on them.

This was the L-1449, which would have been an impressive plane. TWA ordered

25 of them, and looked forward to beating the Seven Seas by late 1956. However,

it turned out that the engines were not working out well in testing, alternative

Allison 501's (the L-1549) would have even worse economics, and thus had to

be replaced with the same R-3350's used on the DC-7C. This, along with Lockheed's

unwillingness to stretch the fuselage to hold more passengers, led to alarming

economic forecasts for the plane, now designated the L-1649A Starliner. However,

Howard Hughes had already committed the funds to allow a big tax break for the

year, and would not allow Lockheed or TWA to cancel the order. Lockheed could

find only two more buyers, and it turned out to be a big money loser. On top

of that, the engine change had caused it to be delayed - not being delivered

until 1957, less than a year away from the first US jets. The final blow was

that it turned out to be slower than the DC-7C, but luckily not by much. However,

the Starliner had one redeeming quality - its unmatched range. This allowed

TWA to provide nonstop service to all European cities from half of the USA,

and its polar service was impressive. Its high allowed loads on these long flights

improved the economics somewhat, but it still turned out to be inferior to those

of the Seven Seas. It was very popular with passengers, though, and was known

as the "Queen of the Skies".

Both the L-1649A and the DC-7C stayed in service after the first jets were delivered, since the jets did not posess the great range of the last propliners. After the first intercontinental jets were delivered in 1960 however (and it became clear that the public much preferred the jets), they were soon relegated to shorter flights and cargo service, the fate of all propliners in the service of the major airlines.

All propliners were eventually sold in the 1960's as shorter range jets took over their routes, and were bought by second tier airlines and cargo outfits. They later found use as water bombers for fighting forest fires, and insect spraying. The last few of the great propliners are still flying today, doing the job they have so ably demonstrated over these many years - getting the load given them to its destination reliably and safely, whether passengers, cargo, or whatever. Many have appeared on the airshow circuit, thrilling fans and youngsters alike with the deep throated roar of their big radial engines. Long may they live!

Tom Gibson

Here is a chronological list of important events in propliner history since the DC-3.

1935 |

The DC-3 is first ordered; designed to compete against the Boeing 247. |

1936 |

DC-3 is first delivered. |

1939 |

The DC-4 is first ordered; designed to allow greater ranges and speeds than the DC-3. |

1940 |

|

1941 |

The L049 is first ordered; designed to compete with the DC-4 (greater speed, pressurization). |

1942 |

|

1943 |

|

1944 |

The DC-6 is first ordered; designed to compete against the L049 (speed and pressurization). |

1945 |

The DC-4 is first delivered to commercial customers. The M202 and CV-240 are first ordered, designed to replace the DC-3. The B377 is first ordered; designed to compete with added luxury and range. |

1946 |

The DC-6 and L049 are first delivered. The L749 is first ordered; designed to compete against the DC-6 (greater range) |

1947 |

The L749 and M202 are first delivered. |

1948 |

The CV-240 is first delivered. |

1949 |

The B377 is first delivered. The DC-6B is first ordered; designed to compete against the L749 (economics, range). The L1049 is first ordered; first airliner fast enough for nonstop US transcon flights. |

1950 |

The M404 is first ordered, designed to compete against the CV-240. The CV-340 is first delivered, designed to compete against the M404. |

1951 |

The DC-6B, L1049 and M404 are first delivered. |

1952 |

The DC-7 is first ordered; designed to compete against the L1049 (nonstop US transcon flights). |

1953 |

The DC-7 is first delivered. The L1049G is first ordered; designed for greater range. The DC-7B is first ordered; designed to compete against the L1049G (range). |

1954 |

The DC-7C is first ordered; first airliner capable of nonstop transatlantic flights in both directions. The F-27 is first ordered, designed to replace the twin pistonliners. The CV-440 is first ordered. |

1955 |

The DC-7B and L-1049G are first delivered. The L1649A is first ordered; designed to compete against the DC-7C (nonstop transatlantic flights). The L-188 is first ordered, medium range turboprop to replace the DC-6B/L-1049. |

1956 |

The DC-7C and CV-440 are first delivered. Last DC-4 used by major US airline (American). |

1957 |

The L1649A is first delivered. |

1958 |

The last piston propliners are delivered. The first L188 and F-27 are delivered. |

1959 |

|

1960 |

|

1961 |

Last B377 used by major US airline (Pan Am). |

1962 |

Last L049 used by major US airline (TWA). The CV-580 is first ordered , designed to upgrade the ConvairLiners |

1963 |

The CV-640 is first ordered. |

1964 |

The first CV-580 is delivered. |

1965 |

The first CV-640 is delivered. Last L1649A used by major US airline (TWA). |

1966 |

Last DC-7 used by major US airline (United). Last DC-7B used by major US airline (Pan Am). |

1967 |

Last L749 used by major US airline (TWA). |

1968 |

Last DC-6 & CV340 used by major US airline (United). Last L1049 & L1049G used by major US airline (Eastern). |

1969 |

|

1970 |

Last DC-6B used by major US airline (United). Last DC-7C used by major US airline (Braniff). |

1977 |

Last L188 used by major US airline (Eastern). |

US Propliner Competition by Aircraft Type

Here is a history of the major US propliners starting with the DC-3. The owners column is not a complete list, and the Last used Airline is the last major US airline that used the aircraft.

Aircraft |

Order Date |

Delivery Date |

Cruise Speed |

Range |

US Transcon |

Stops |

T/O Weight |

Description |

|||||||

Original major US/International owners |

Last used |

Airline |

|||||

Long Range Aircraft |

|||||||

DC-3 |

6/35 |

6/36 |

170 mph |

1,025 Stat. mi |

17 hrs |

3 |

28,000 lbs |

Produced in Response to Boeing 247 by TWA |

|||||||

Virtually all US airlines except National |

1961 |

Delta |

|||||

DC-4 |

8/39 |

11/45 |

227 |

2,500 |

14 |

1 |

73,000 |

The first US postwar airliner, sponsored by AAL, UAL, EAL. |

|||||||

American, United, Eastern, TWA, Delta, Braniff |

1956 |

American |

|||||

L-049 |

1939 |

11/45 |

313 |

2925 |

11 |

1 |

86,250 |

Produced in response to DC-4 by TWA, pressurized. |

|||||||

TWA, Pan American, American Overseas |

1962 |

TWA |

|||||

DC-6 |

9/44 |

11/46 |

328 |

3340 |

10 |

1 |

97,200 |

Produced in response to the L-049 |

|||||||

United, American, National, Delta, Braniff |

1968 |

United |

|||||

L-749 |

1946? |

6/47 |

324 |

4845 |

10 |

1 |

107,000 |

Produced in response to the DC-6 |

|||||||

TWA, Eastern, KLM, Air France, |

1967 |

TWA |

|||||

B377 |

11/45 |

1/49 |

340 |

2750 |

10 |

1 |

142,500 |

United, Pan American, Northwest, Am. Overseas, BOAC |

1961 |

Pan Am |

|||||

DC-6B |

10/49 |

4/51 |

315 |

2925 |

10 |

1 |

107,000 |

Produced in response to the L-749 and B-377 |

|||||||

Almost all major US airlines except TWA, Braniff, & Delta |

1970 |

United |

|||||

L-1049 |

4/50 |

11/51 |

301 |

4700 |

9 |

0 |

120,000 |

Produced in response to DC-6B; first nonstop US transcon flights |

|||||||

TWA, Eastern |

1968 |

Eastern |

|||||

DC-7 |

1/52 |

10/53 |

359 |

2850 |

8 |

0 |

122,200 |

Produced in response to L-1049; also flew nonstop US transcons |

|||||||

American, United, Delta, National |

1966 |

United |

|||||

L-1049G |

1953? |

1/55 |

311 |

4815 |

9 |

0 |

137,500 |

Produced in response to the DC-7 |

|||||||

TWA, Eastern, Northwest, National, Air France, Lufthansa |

1968 |

Eastern |

|||||

DC-7B |

1953? |

5/55 |

360 |

4920 |

8 |

0 |

126,000 |

Produced in response to L-1049G (increased range) |

|||||||

Pan American, PANAGRA, American, Delta, National |

1966 |

Pan Am |

|||||

DC-7C |

6/54 |

6/56 |

355 |

5640 |

8 |

0 |

143,000 |

Produced to fly the Atlantic non-stop |

|||||||

Pan American, Northwest, BOAC, KLM, SAS, SABENA |

1970 |

Braniff |

|||||

L-1649A |

1955 |

1957 |

342 |

6885 |

8 |

0 |

156,000 |

Produced to compete with the DC-7C (comfort, range) |

|||||||

TWA, Air France, Lufthansa |

1965 |

TWA |

|||||

L-188 |

6/55 |

10/58 |

385 |

2500 |

7.5 |

0 |

116,000 |

Produced for medium stage lengths. |

|||||||

American, Eastern, National, Braniff, Northwest, Western |

1977 |

Eastern |

|||||

Short Range Aircraft |

|||||||

CV-240 |

9/45 |

2/48 |

270 |

1000 |

41,790 |

||

Produced to compete with the M202 |

|||||||

American, Continental, Pan American, Western |

1964 |

American |

|||||

M202 |

11/45 |

8/47 |

277 |

1000 |

39,900 |

||

Produced as a DC-3 replacement. |

|||||||

Northwest, TWA |

1959 |

TWA |

|||||

M404 |

2/50 |

11/51 |

280 |

1700 |

44,900 |

||

Produced to compete with the CV-240 |

|||||||

TWA, Eastern |

1962 |

Eastern |

|||||

CV-340 |

1950? |

3/52 |

284 |

1800 |

47,000 |

||

Produced to compete with the M404 |

|||||||

United, Braniff, Continental, Delta, National, Northeast |

1968 |

United |

|||||

CV-440 |

1954? |

2/56 |

300 |

1800 |

49,700 |

||

Produced to improve the CV-340 |

|||||||

Eastern, Continental, National, Braniff, Delta |

1970 |

Eastern |

|||||

F-27 |

1954? |

7/58 |

296 |

1082 |

45,000 |

||

Produced to replace the piston twins. |

|||||||

Pacific, Bonanza, West Coast, Mohawk, Ozark, Piedmont |

1980 |

Ozark |

|||||

CV-580 |

1962? |

4/64 |

324 |

1540 |

53,200 |

||

Produced to upgrade the ConvairLiners |

|||||||

Frontier, North Central, Allegheny, Lake Central |

1986? |

Northwest |

|||||

CV-640 |

1963? |

11/65 |

300 |

2300 |

53,200 |

||

Produced to upgrade the ConvairLiners (CV-600 & CV-640) |

|||||||

Trans-Texas, Hawaiian, Caribair |

1978 |

Texas Intl. |

|||||